Our History: Raising the Barre Since 1969

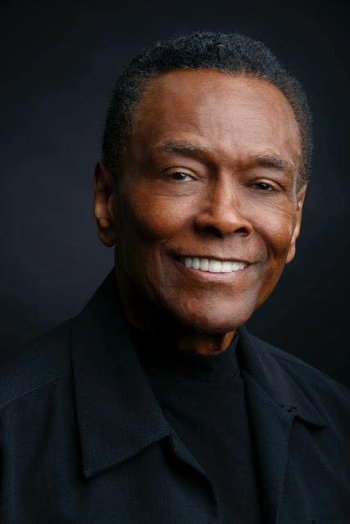

Watch Arthur Mitchell: A Day of Reflection

In 1969, at the height of the civil rights movement, Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook founded Dance Theatre of Harlem. Their vision remains one of the most democratic in dance.

In moments of extreme injustice and frustration the most impactful art is born. This is true of the inception of one of the most influential American ballet companies of the last five decades, Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Arthur Mitchell created the company in New York City, after making history in 1955 as the first black principal dancer at New York City Ballet. He was also the famed protégé of George Balanchine—the Russian-born dancer, choreographer and co-founder of the School of American Ballet. Mitchell’s impulse to start Dance Theatre of Harlem is said to have been spurred by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968.

Working in Brazil on a commission from the American government to assist in the founding of the National Ballet of Brazil, Mitchell decided to return to the US to try to make a difference in his community by teaching ballet classes in his native Harlem. At the height of the civil rights movement, in a graceful moment of artistic resistance, he created a haven for dancers of all colors who craved training, performance experience and an opportunity to excel in the classical ballet world.

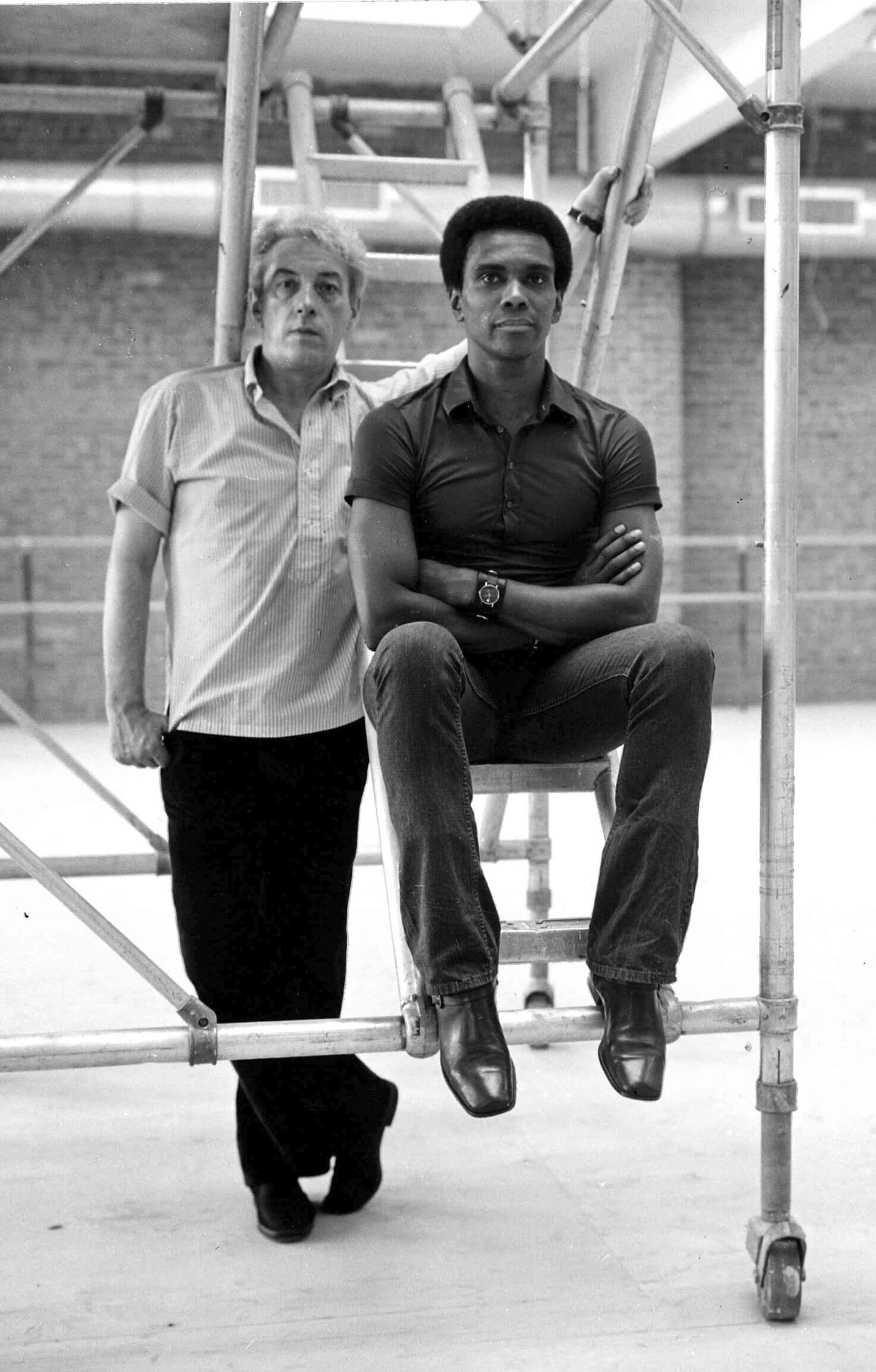

The early days were humble and inclusive. Mitchell began by teaching dance in a converted garage in Harlem, leaving the doors open so passersby could see what was going on. He relaxed the dress code to encourage enrollment by young men who preferred to dance in jean shorts and T-shirts. To accommodate his growing roster of students, he eventually partnered with his former ballet master Karel Shook to help him run the school and direct what would eventually become Dance Theatre of Harlem. The company would grow to have a lasting impact on the American ballet scene and become a beacon for black dancers worldwide. It was a pioneer in the dance world, integrating stages and spreading the art of ballet through massive outreach programs at home and abroad.

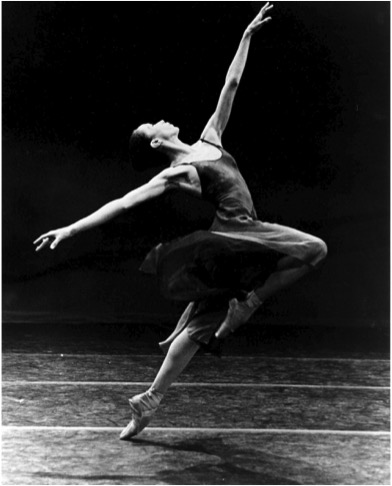

A budding ballerina named Virginia Johnson met Mitchell while a student at the NYU School of the Arts and became a founding member of Dance Theatre of Harlem and, later, its artistic director. “In that first company we were an extremely diverse group of people,” Johnson says of the early days. “We were Asian, Mexican, black… I think the first white dancer didn’t come until 1970. But it was not about making a ‘black ballet company.’” She continues, “It was to make people aware of the fact that this beautiful art form actually belongs to and can be done by anyone. Arthur Mitchell created this space for a lot of people who had been told, ‘You can’t do this,’ to give them a chance to do what they dreamed of doing.”

The company gained momentum in the midst of the Black Power movement, Johnson recalls. “But there wasn’t a sense of militancy around the idea of making black people visible in this art form. It was more that he made dancers aware of the fact that they could define their own identity. That they didn’t have to be defined by somebody else’s perception of them.”

The roots of ballet are steeped in the Renaissance and Baroque eras in Europe, specifically France under the decadent rule of Louis XIV. Ballet was created for nobility, to be performed by nobility, and it took many years for the art form to become accessible to the wider public. Even today, it is performed by a select and well-trained few. By the 19th century, ballet had spread from France to the world stage and grew as a technique in Europe and the Americas. If for no other reason than the intense training required and the elaborate aesthetics, ballet remained exclusive for several hundred years. Perhaps because so much of the early form was devoted to portraying the European idealist outlook and history, the assumption was often made that non-white dancers could not understand or embody something presumed alien to them.

The America into which Mitchell was born in 1934 was rife with racial division. This atmosphere dominated the dance worlds too, offering little opportunity for dancers of color to study and flourish in classical ballet. One of the people trying to expand the art form and promote integration was George Balanchine, who would later become a mentor to Arthur Mitchell. In 1933, the dancer Lincoln Kirstein wrote a letter to a director in Hartford, Connecticut introducing his new friend, Balanchine, and their joint aspirations to start a ballet. Kirstein called for a core of “16 dancers, half women, half men, half white and half negro.” What resulted was the creation of the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet, founded by Kirstein and Balanchine. However, their joint plan for student diversity was never realized: Administrative forces that opposed the idea of an integrated ballet company consistently blocked them.

Despite resistance, Balanchine managed to bring several black dancers in as guest artists. He created The Figure in the Carpet for the famed Martha Graham–trained dancer Mary Hinkson in 1960, and choreographer Louis Johnson performed with the company in the 1950s, among others.

Although Mitchell is often credited as the first black ballet dancer in NYCB, a little-known dancer named Arthur Bell was a student at the School of American Ballet in the late 1940s and performed with NYCB before making a career for himself in Europe. His story was all but forgotten by history when, in 1994, a reporter found him living in a homeless shelter, alone and destitute. Sadly, his story highlights the lack of opportunity faced by many black dancers after retirement.

Mitchell had found his path to ballet as a young boy in Harlem. His mother enrolled him in tap classes at the Police Athletic League. A guidance counselor encouraged him to audition for the High School of Performing Arts, where he was encouraged to pursue ballet. He excelled at it, earning a scholarship to the School of American Ballet soon after graduation. Mitchell met Balanchine at the school and within a few years was invited to join the company.

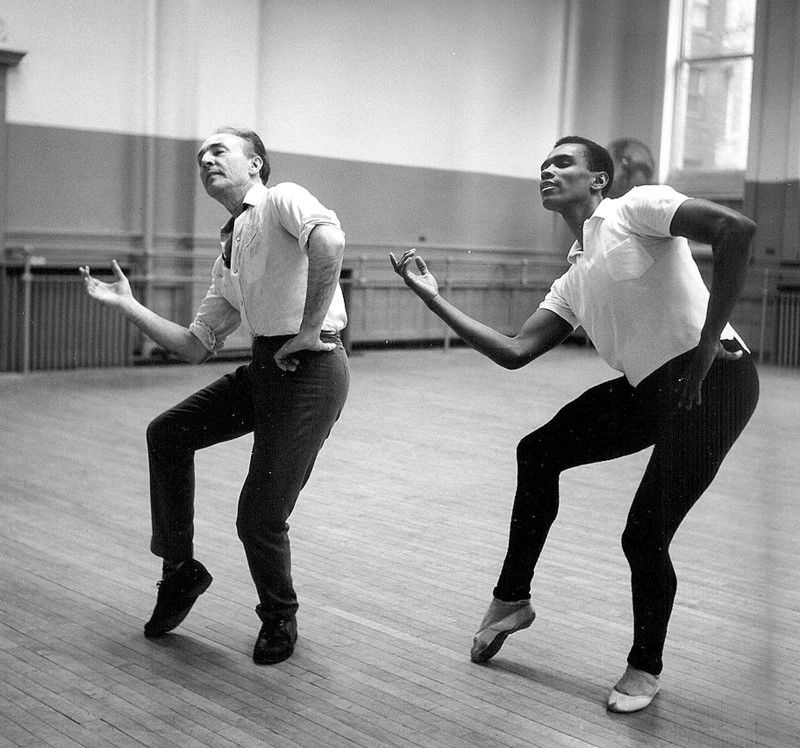

“Balanchine was interested in African-American dancers, but Mitchell was not just a dancer to him,” Johnson recalls. “He was the realization of an idea that Balanchine had wanted to explore. When Mitchell joined NYCB, it released something in Balanchine. He started creating some of his greatest work—a different kind of work, something he’d been wanting to do for some time.”

Balanchine choreographed specific roles for Mitchell when he was a principal at NYCB, including the world-renowned and groundbreaking pas de deux in Agon, and the role of Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Balanchine knew what many great choreographers know: that some of the best work is inspired not just by a great technical dancer, but by a well-rounded individual that can offer their own insight into the execution of the choreography.

In 1971, Dance Theatre of Harlem, billed as a “neo-classical ballet company,” officially debuted at the Guggenheim Museum to great acclaim. Later the same year, Balanchine and Mitchell co-choreographed the piece Concerto for a Jazz Band and Orchestra, which offered an unprecedented collaboration coupled with a platform for the emerging Harlem-based company. After a prizewinning television special that Mitchell choreographed, Rythmetron, the company had their first full season in New York in 1974.

Mitchell rose to fame as a principal dancer with NYCB from 1956 to 1969. When he left, he seemed to rebel against the homogenous world he had been immersed in, envisioning a larger space for dancers like himself to thrive. Virginia Johnson recalls, “Right from the beginning it was about diversity in the richness, which was very oppositional to the way that ballet was moving in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s in this country. At that time, ‘sameness’ was what was signified in ballet. One of the things that Arthur Mitchell was doing was creating the chance for people who had the skill—and the training—to perform, to keep challenging themselves, and to grow into world-class artists, which was not something that was happening in many other places.”

When Mitchell began Dance Theatre of Harlem, Balanchine gave him the rights to several ballets. This afforded Mitchell a repertoire of recognizable modern classics for his programs, which was invaluable for the fledgling company. Mitchell started Dance Theatre of Harlem with a strong base, and by 1979 it was touring internationally with a repertoire of 46 ballets. In the 1980s, the company reached the forefront of the American ballet scene by carving a niche for themselves and infusing new life into works like Firebird, Giselle, Scheherazade, Bugaku and the infamous Agon.

Through the 1990s, Dance Theatre of Harlem continued to break racial and political boundaries, to worldwide acclaim. They were the first American ballet company to perform in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union, and in 1992, they made an international statement on their tour to South Africa at the tail end of apartheid. The company performed to a mixed crowd and brought their outreach principles to the townships, creating a dance program that still thrives today as Dancing Through Barriers. This remains an excellent example of the impact a predominantly black and brown ballet company could make on international politics, challenging antiquated racist constructs through the simple act of practicing and sharing their art.

After 25 years as a principal dancer with the company (and a 40-year international career), Virginia Johnson returned to fill Mitchell’s shoes as the company’s artistic director in 2013. “When Arthur Mitchell invited me to step into his huge shoes, I really didn’t want to,” she says. “But I knew that the work needed to continue. There’s a particular challenge right now. In 1968 and 1980 and 1990, the novelty of Dance Theatre of Harlem and the extreme difference of the experience was something that was very powerful, whether audiences were used to going to the ballet or not. Nowadays, we’re in an electronic age where we don’t really understand or even appreciate the notion of the live performance of an art form that is so rigorous. One that requires actually coming into the theater.”

Dance Theatre of Harlem went on hiatus due to financial difficulties from 2004 to 2012. “This means that there was a generation of little girls who didn’t see brown ballerinas,” Johnson says. “They didn’t have that seed planted of I could be up there too! I want to be a part of that! So we really need to rebuild that sense of inspiring another generation of dancers to come forward.”

Johnson has been instrumental in helping usher the company into a new era while maintaining the old legacy. Dance Theatre of Harlem is not just a ballet company or groundbreaking cultural institution, but an elegant example of what is possible when an inclusive approach to art is allowed to evolve and thrive.

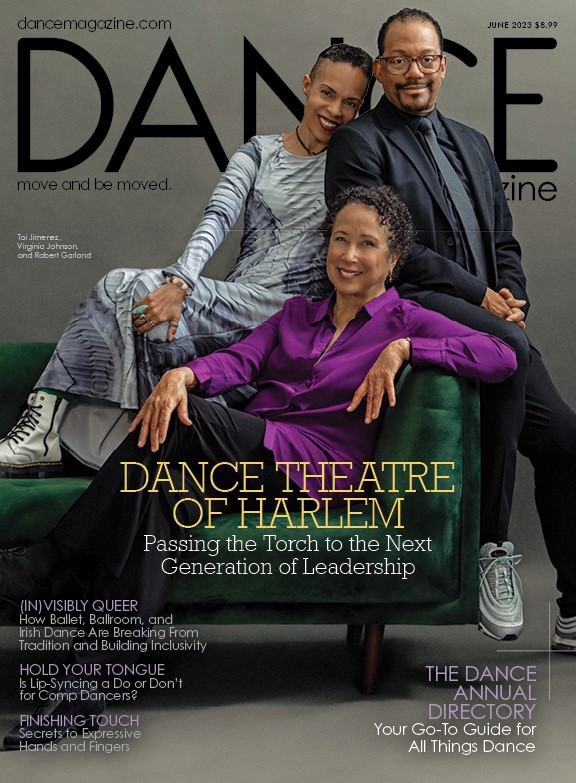

Bringing to a close a four decade-long chapter of dance history, Dance Theatre of Harlem Artistic Director Virginia Johnson has announced her retirement from the visionary company, set for the close of the 2022-23 season on June 30, 2023. Her tenure with this powerful presence in the world of ballet includes twelve years in her current role as Artistic Director, preceded by a staggering 28 years as a company member, highlighted by her distinction as a founding member and as a Principal Dancer. As Ms. Johnson becomes Artistic Director Emerita, she will be succeeded as Artistic Director by current acclaimed DTH Resident Choreographer and School Director Robert Garland. Mr. Garland will continue in his current roles until he assumes the role of Artistic Director on July 1, 2023, at which time former DTH Principal Dancer Tai Jimenez, who following 12 years dancing with DTH became the first Black ballerina elevated to Principal at Boston Ballet in 2006, will become Director of the Dance Theatre of Harlem School.

Join us as we continue to uphold our values of access, opportunity and excellence!