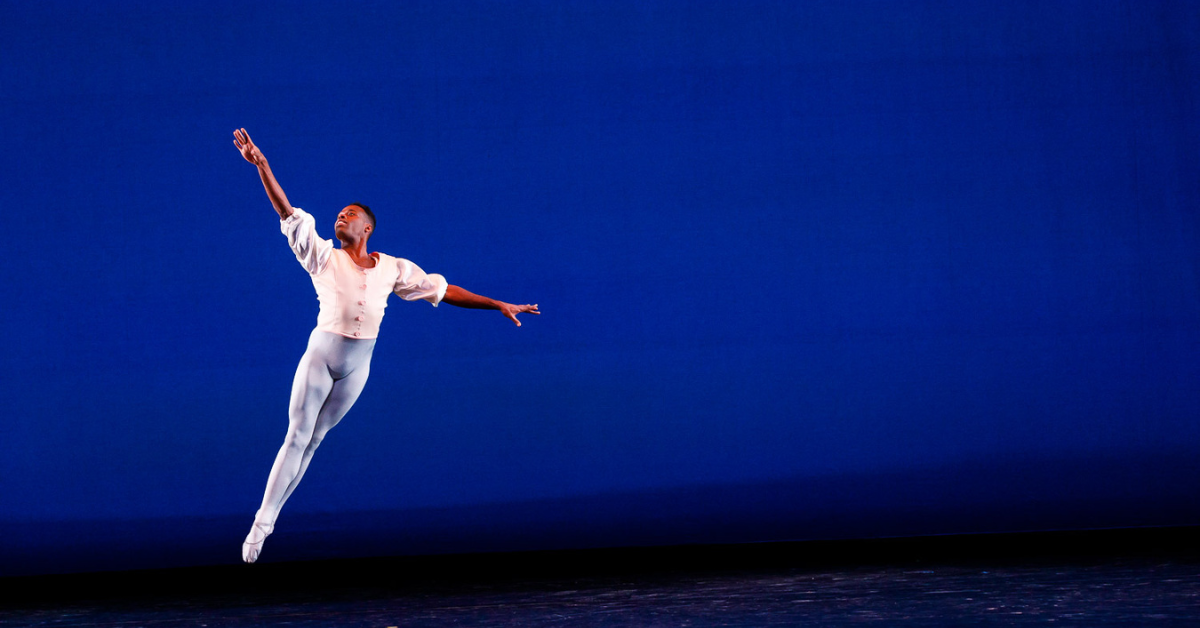

A Childhood Dream Fulfilled: Christopher Charles McDaniel

No stranger to Dance Theatre of Harlem, Christopher Charles McDaniel has taken on many roles in the organization for more than twenty years. Born and raised in Harlem, he first saw the company in a Lecture Demonstration at CUNY’s Aaron Davis Hall. Now, as he is retiring from his Company Artist position, he reflects on how and why Arthur Mitchell and Dance Theatre of Harlem have impacted his life thus far.

How were you first introduced to Dance Theatre of Harlem?

I was introduced to Dance Theatre Harlem on a school field trip in 1999. My school went to see a Lecture Demonstration, and it was the first time I ever saw ballet. Being from East Harlem I always saw fliers and posters for Dance Theatre of Harlem. Even in some of the TV shows that I used to watch there would be a random poster in the back of a scene, like Sister, Sister and A Different World.

I saw my initial Lecture Demonstration at Aaron Davis Hall, and I remember the person leading the program saying that there is a school during the social dance portion. I remember him saying that if you want to dance, tell your mom or guardian to call the school and say that you want to audition. I begged the assistant principal, Ms. Camiolo, to set up an audition. Ms. Camiolo said, I will get you an audition if you stop fighting and you keep your grades up. So, I became a little angel child. A couple of years later I auditioned when I was 10 years old and started officially when I was able to get to DTH by myself on the bus from East Harlem.

What are some of your fondest memories of being a student at Dance Theatre of Harlem?

I started in a class of twenty-four other boys. It was a huge boys class. It never seemed unorthodox to do ballet as a black boy, it just seemed like another thing that we did. I also did not know that ballet was a white art form, because the way I was introduced to it was with people who looked like me. It is a really fond memory, in hindsight, never feeling like ballet was something to be ashamed of.

Other than being in a class with like-minded boys, having live music (a pianist), the discipline of it, and the responsibility were great. I vividly remember on my very first day getting to the studio way too early, because I went straight from school, and Laveen Naidu (former DTH dancer and director of the DTH school) was like did you even eat? – I hadn’t. I didn’t have any money. He went into his pocket and gave the receptionist some money and took me to the deli and bought me a sandwich. That’s how I started off at DTH, being taken care of. That was really encouraging. To be in a place that cared about my well-being before they even saw me as a student. Doing the end-of-year performance, being onstage with lights, and all of that was amazing. The first two or three years we did it at the United Palace Theatre, where they are holding the Tony Awards this year. Getting to be on a big stage was amazing, going through the whole process of seeing everyone doing makeup, warming up, and seeing company people going past us backstage.

Darryl Quinton had a ballet that he made for the Professional Training Program called “When The Teacher Leaves The Room.” It was really funny and jazzy. He incorporated 50 Cent’s In Da Club. The teacher left the room and the [students] started playing music and dancing around. It was connecting to something. That song was so popular at that time. We were hearing this song that kids were listening to on the radio, in this big theater and the dancers had on school uniforms. Most of us wore uniforms to school, so we were seeing our own lives. I remember seeing Erica (her name still sticks with me) doing these amazing fouetté turns, not that I knew what they were back then. When you’re a kid and you see someone just spinning around like that, it’s just mind-blowing. So really my fondest memories are being thrust into this art form, being surrounded by beauty. Getting to see it so up close and personal. I was watching the company all the time. I was the kid that got to the studio early and would sit in front of the room and watch the company rehearse. So I saw Return really early in its time, I saw New Bach right when it premiered, and South African Suite. A lot of these ballets that I ended up dancing, I saw the company do when I was a student.

You are one of the few people in the current company that’s worked with Arthur Mitchell extensively. What was that experience like and how did it shape the way you approach ballet?

Working with Mr. Mitchell was like meeting a hero, and having him be way better than you expected. When I was a kid, he would just kind of show up, there was no warning that Arthur Mitchell was in the building or that he was going to take over your class. If he came in and he saw something, he said something, and the class was his. Period. Whoever was teaching would then just become the teacher’s assistant. All of the teachers had this great admiration and respect for him. No matter if they were the ones teaching the class or not, if he came in and took over the class, they went with it and we all got on one accord.

I remember instantly figuring out that he has one of those personalities that was kind of harsh at times, but he loved kids, he loved the boys class, and he loved making us compete with each other.

Even if he wasn’t in the room, if I danced as if Arthur Mitchell was standing in the corner I would always get positive feedback from the teachers. At that point in my life, I felt that nobody was really giving me positive feedback about myself. I only heard negative things about how I was sassy, short, or dark-skinned. When I got to DTH and a teacher said “Christopher is really smart because he learns the combinations quickly”, or, “he jumps really high”, I found there were things that made me special- it made me feel that I had value. So even if Arthur Mitchell wasn’t there, I knew he felt those things about me. so I had to keep it up and show that all the time. It was great having this person whose word was the end all be all in that building. Because he felt that I was good, or I was getting it, I felt like I could do this.

You have worked with Ballet San Antonio, Los Angeles Ballet, and Dance Theatre of Harlem to name a few. What are some of the biggest differences in working in white spaces vs black spaces?

The positives of working in places like LA Ballet and Ballet San Antonio were that the infrastructure was more established. There were certain people in place to give you things that you needed. For example, at LA Ballet I wanted to do a lot of Balanchine ballets, full-length ballets, and have a presence in the city that I was living in. Because at the time, dancing for the Ensemble in New York we never performed in New York, we didn’t do a New York Season. We did Open Houses in the studio, but we didn’t have an Ensemble season in New York. So I felt like no one knew we were there. At LA Ballet we were in our own city. The director, Colleen Neary, was a repetiteur for the Balanchine Trust. We were getting to do a lot of Balanchine ballets that I wasn’t getting at Dance Theatre, and that changed how I dance. Dancing Balanchine really teaches you a lot about yourself as a dancer. A lot of things you need to develop, you start to develop in the process. Additionally, because I was a strong dancer in the company, it gave them the space to ask me to teach for the school. On the negative side, I was the only black dancer in the company for a while. There were several microaggressions that I had to deal with, comments about my hair or my skin color under certain lighting. Doing certain roles, or not being able to do certain roles because I was black. Not having anyone I could rely on to stand in the gap for me. That eventually took its toll. I felt like I was in it alone.

The first thing I saw on Ballet San Antonio’s website was that the company manager was a beautiful black woman with an afro, Danielle Campbell. I initially went in as a guest artist. I was the only black dancer, but at that point, I felt established as a leading dancer and that I wouldn’t have to deal with certain microaggressions because the company manager was a black woman and she was someone in power who I assumed would step up for me when needed. That is exactly what it was. From the beginning, she was a source of encouragement and nursed me back to health from all the stuff I had dealt with at LA Ballet. She stood up for me and gave me the opportunity to teach and do outreach at the Boys and Girls Club.

Arthur Mitchell prepared me for it. He said to me, I don’t know when the company is coming back, I would obviously love for you to stick around here, but I need you to go out into the world and really get the experience that you need. Wherever you go, you’re going to end up being the only black person. You’re going to have several issues because they are going to look at your feet and treat you a certain way. That was when he gave me the fake arches, he told me certain colors of [lighting] gels that were better for my skin tone. He warned me about certain things that he had gone through as they pertained to racism and roles. It was amazing to have the man that really started it all give me that heads-up.

I think those experiences built me up in such a way that I was able to set boundaries for myself and only agree to things that I wanted to do.

You are retiring at the end of the season. What helped you make peace with that decision? Was it hard to make that choice?

What helped me make peace was just reflecting on the initial goal that I said out loud as a child, I want to be a principal dancer with Dance Theatre of Harlem. I am getting to the point in my career where I have done several leading roles, have taught at different places, and have been able to choreograph. I felt like I was in a place where I have done more than what I set out to do. I was just really grateful. I have students that are being promoted in major companies, like New York City Ballet and Carolina Ballet, getting into several different colleges. It makes me feel like I am making an impact beyond the stage. Mr. Mitchell always said that we are in service to the art form. I feel like if I stay on stage, I am just being selfish and trying to soak up more glory and applause. I don’t want to do as much physical strain to my body to dance at the level that can sustain a triple bill of Allegro Brillante, Garland, and Forsythe. So I made peace with it. I think there’s going to be a mourning period of course because it’s what I’ve known for over twenty years.

During the pandemic I was able to lead a group of dancers through productions online, producing videos, making online content, and DTH on Demand. Working with the marketing department, the development team, and the executive staff, I was trusted to suggest ideas that would keep us [DTH] going. It’s another one of those Arthur Mitchell things, where I saw him have his hand in several different pots. And then I looked at Robert Garland who was the Resident Choreographer, but he was teaching in the school, directing the school, he was the webmaster, he was editing music, helping people figure out their costuming. I knew I had to keep myself valuable to the organization. But it doesn’t have to be just at DTH or any one place. I know that this is my skill set that I built over years of experience and I can take that with me anywhere. I want to teach others how to do the same thing because, at the end of the day, it’s not about just me but about building our community up even more. I think a lot of dancers hold on to dancing because they haven’t quite identified another love, or another passion, or had the opportunity to develop that.

What advice do you have for young male dancers of color?

Go to the theater. I think the best thing that they can do is to surround themselves with the craft. If you want to be a dancer, you need to see as much dance as possible. You need to see what other dancers are doing, even if you are not seeing dancers that look like you. Find the things that get other dancers the most acclaim, get them featured, or get promoted. If you see a lot of dance you are building your education, you are building knowledge. It keeps you inspired. Additionally, the physicality of it. Young dancers have to know that there’s a big workload ahead to do this. While we are in a place where everyone has the right to say no, and everyone has body autonomy, you have to understand there will be a sacrifice in this. Someone is going to tell you to stretch, to work out, to do pilates. You need to be open to doing that.

Photo Credits: Christopher Charles McDaniel in Allegro Brillante, photo by Theik Smith;Students rehearsing Dougla (2005), photo by Matine Bisagni; Christopher Charles McDaniel in Allegro Brillante, photo by Theik Smith; Christopher Charles McDaniel and Amanda Smith in Allegro Brillante, photo by Theik Smith